A Trip to the Fair

Editors’ note: For additional context on the origin of the following essay, as well as a reflection on the launch event for Huellas’ third volume, please read this note by author, published one year later.

—

Alvaro was surprised to hear Rafa on the other end of his office phone. They hadn’t spoken since November, around the time of his father’s death. Rafa asked about the family, and about Señora Isabel, his mother. After catching up on the latest, Rafa revealed the reason for the call, “Hagame un catorce, hermano. I need help taking tourists from Miami to the World’s Fair.”

“To the World’s Fair in New York?”

“Yes, to New York in late April. There’s plenty of time to make arrangements. You’re the best driver I know. You’re also excellent with directions.”

Rafa knew how to be persuasive.

Rafael Buitrago owned Viajes Mundo, a travel agency with offices in Bogotá and Miami. He had an upcoming road trip to the grand opening of the 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows Park. Flying was expensive. For many, driving tours were an affordable alternative. Rafa quickly found himself with ten bookings and in need of two cars. Getting a second car was easy. There were plenty of snowbirds looking for someone to drive their car north in the spring, but getting a dependable second driver was not easy. That is, until Alvaro came to mind. Rafa knew he was good enough to dabble in rally racing, and that he had a commercial license, but he was married now with a handful of children. Alvaro was a long shot.

After hanging up the phone, Alvaro tried to focus on his work, but Rafa’s offer was all consuming. Every once in a while, he punched random numbers on his adding machine, ripping the curling paper tape and flinging it toward the bin, just to do something to pass the time. Little got done the rest of the afternoon. He was anxious to leave the office, to walk out to the streets of downtown Bogotá and to his car where he could be alone. An all-expenses-paid trip to the U.S., and a World’s Fair opening-day ticket to boot, was worth mulling over.

Isabel was still en luto, mourning her husband’s unexpected death. Alvaro was as concerned about his mother’s reaction to the trip as he was of his wife’s. Yes, his father’s recent passing complicated things, but he also felt freer to make his own decision, accountable to one less person, one likely to have a strong opinion about the matter.

After wrestling with the proposition for a few days, he concluded that Rafa’s offer was too good to pass up. Getting ten days off was fairly easy. He was well liked at the office, and his boss assented without much convincing. Isabel left it up to him, offering no resistance. He knew his wife would be resentful about shouldering the load of caring for five all under seven while he was away, but he also knew she would slowly come around. She wasn’t obstinate the way he was. He reminded her about his dream to one day emigrate north as a family, and how he could turn the trip, a free trip, into a scouting mission. He was only going to be away for ten days, a fact he repeated multiple times to convince her — and convince himself — that everything would work out fine, that the trip was doable. And, if his mother-in-law came to help, the kids wouldn’t even notice his absence. Alvaro also knew how to be persuasive.

When he called Rafa back to tell him he was signing on, Rafa was incredulous, “I didn’t think you were going to do it,” he said with delight. “After I hung up, I thought about all your little ones, and I presumed you were out.”

Alvaro had been caught in America’s gravitational pull for some time. He was thirty-one and the difficulties of living in Bogotá, even with a decent job, were grating on him. He worried about shortages of milk and other basics for his children; he abhorred the lack of civility, the petty crime, and the random lawlessness that sometimes led to violence, some of it political, but much of it opportunistic. Rafa’s offer couldn’t have come at a better time. He was ready to try something else, ready to see if what was said about America was true, that it was the real El Dorado, where the trains run underground and the buildings scrape the sky, where the latest models roll on six-lane highways and engineering marvels span wide rivers. He would have twelve-hundred miles to verify it all.

Saturday, April 18, 1964 — Miami, Florida

Alvaro landed in Miami on Saturday, the day before the start of the drive. Rafa picked him up at the airport, relieved to have his co-pilot present and accounted for. He had been in Miami securing the two vehicles, getting them inspected for the long drive. That afternoon, they drove out to the Hialeah Racetrack, a favorite pastime for both. In between races, they went over the plans. Rafa would drive the lead car with Alvaro following in the second. The caravan was to cover twelve-hundred miles in three days, with two overnight stays, Sunday night in Charleston, South Carolina, and Monday night in Washington D.C., where they would do a little sightseeing before heading north. It was imperative they reach New York by Tuesday night, the night before opening day.

Alvaro went to bed early, but he had trouble falling asleep. Scenes from Hialeah kept repeating in his head, the powerful thoroughbreds urged on by tiny men in colorful silks, the dollars, by the handfuls, pushed through the cashiers’ windows, the women in the stands, tall and dressed like Jacqueline Kennedy, and the rumble of the crowd rising as the horses entered the homestretch. To top it off, the weather had been glorious, sunny in the mid-seventies. It wasn’t like what he had dreamed, it was better.

As he tossed and turned, he imagined the vistas along the way. His mind racing to New York City, the Empire State Building and the Statue of Liberty swirling in his head. He was counting on his driving skills compensating for the lack of familiarity with the roads. He prayed the cars could handle the miles. His nightmare was to be stuck on the side of the highway, babysitting a blown radiator and five anxious tourists, not knowing enough English to ask for help when the patrolman came. He worried about getting separated from Rafa, and he had no way to assess whether arriving by Tuesday night was doable or not. He thought about his mother. He thought about his wife and kids, probably asleep by now, hoping nothing out of the ordinary was stirring back home.

Sunday, April 19, 1964 — Miami to Charleston

Rafa and Alvaro were up very early Sunday morning. The meeting time with the passengers had been set for 5 A.M., about an hour before sunrise. In the dark, one by one, or two by two for the couples, the travelers arrived at the meeting spot. Rafa took care of the check-in while Alvaro methodically loaded the luggage, small pieces in the back, the rest on the luggage racks that he tied down with strong rope. Rafa did the introductions all around, everyone greeting their new traveling partners. He split the group so that the two couples and one single traveler went with him in the smaller Oldsmobile Dynamic 88. It was easier for the couples to share smaller spaces. The five other travelers went with Alvaro in the 1962 Ford Station Wagon. Both vehicles were big cruisers, but packed with six adults each, the ride was going to be cramped.

After the initial excitement in the parking lot, the car turned quiet at this early hour. They were escorted out of town by a beautiful Miami dawn, the sun rising over the Atlantic on the passenger’s side. Señora Clemencia had taken a liking to Alvaro and took the front seat. She liked that he was polite, and not brusque like so many career drivers. She reminded him of his mother, tall, proper, and well-dressed. She kept the conversation going for miles, the chit chat helping to dissolve time.

The caravan rode US Route 1 to Jacksonville, where they stopped for a late afternoon dinner. The drivers, glad to have most of the long Florida peninsula behind them, needed the longer break. Unlike the passengers, who snoozed in the car, Rafa and Alvaro had put in four hundred miles of alert driving. Rafa was concerned about being behind schedule, despite pushing the pace. They were losing too much time at the refueling stops. It wasn’t easy herding ten travelers, keeping them from wandering off to stretch their legs while waiting for the others to go to the bathroom.

By the time they left Jacksonville, the evening was settling in, but everyone was full and rested. They switched to the Coastal Highway (Route 17) for the remaining thirty miles into Georgia. From the border, they had about two-hundred miles to Charleston. Driving in the dark was tough, especially for Rafa in the lead car.

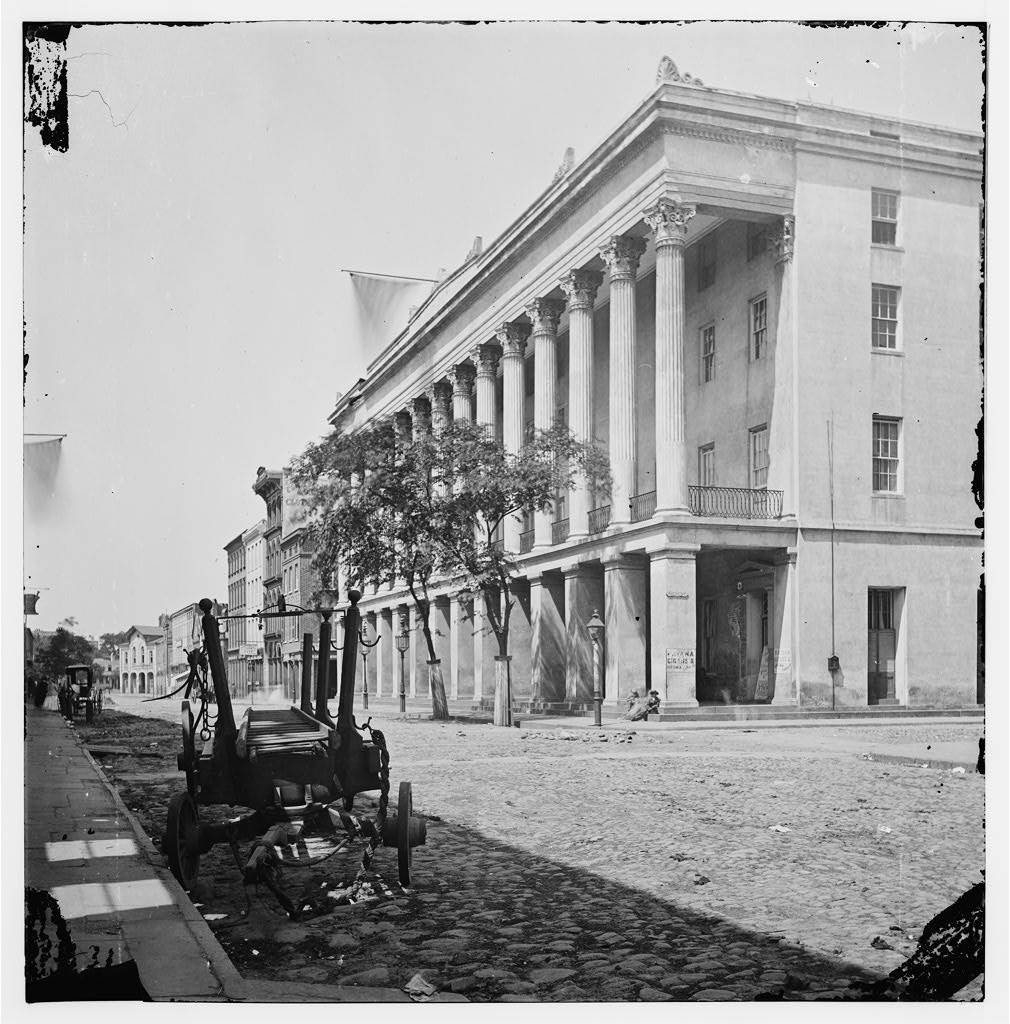

Rafa’s itinerary included a stay at the iconic The Charleston Hotel, but a different hotel was at the address. It turned out The Charleston Hotel, with its double colonnade, had been demolished a few years earlier, replaced by a motor inn with a similar name. The bargain room rate now made sense.

Thankfully for Rafa, the tourists were too exhausted to care. As long as there was a bed, nothing else mattered. With only the nighttime receptionist on duty, the check-in at the motor inn was agonizingly slow. Rafa, with paperwork in hand, diligently squared away the details in the office while Alvaro unloaded the bags, each passenger picking up theirs, and saying good night once they were handed their room key. With his last reserves, Alvaro carried Señora Clemencia’s bag to her room, before crashing in the room he and Rafa shared. Everyone wanted to rest and get ready for the trek to Washington D.C. the next morning. Sleep came fast, Alvaro was too tired to think about the long day.

Monday, April 20, 1964 — Charleston to Washington D.C.

The late night led to a sluggish start. It was another sunny morning, but considerably cooler than Miami’s. Despite Rafa’s prodding, the group plodded through breakfast, and by the time they checked out of their rooms and packed the cars, a good part of the morning had been lost.

Once on the road, they took Route 17 along the coast towards Wilmington, North Carolina. The road was pastoral beauty on one side and beach towns on the other, with the fresh green of spring everywhere.

The passengers had taken turns sitting in the front seat the previous day. This morning, Señora Clemencia was back in the front. She asked him about his wife and the children. She expressed surprise that such a young man already had five children. A good Catholic boy, she said, embarrassing him a little. He told her the story of how he met his wife at the funeral of a friend who had died in a tragic accident walking past a construction site. His wife’s brother also happened to be the unlucky fellow’s friend. He then told her a little bit about each of the kids. Others, now feeling more familiar, joined in adding their own stories. Soon the conversation turned to living in America. Those in the U.S. with green cards offered advice and tips to those without one. One maxim had general consensus: the importance of learning English, otherwise the gringos think you’re dumb.

The chatter was frequently interrupted by a passenger calling out a sight or a landmark to be admired by all. Near Wilmington they came across an iron bridge of an unusual design that greatly impressed Alvaro. He slowed down to take in the engineering feat, marveling at the iron beams and struts and the massiveness of the structure, calling out the American ingenuity — esos gringos son muy avispados.

On the other side of Wilmington, they stopped for gas and a late lunch. Rafa, studying the map, updated his estimates, concluding they would get into D.C. after sundown, but not too late. He was trying to avoid another late night arrival like the previous night’s into Charleston.

Alvaro, with the map unfolded in front of him, and in a sudden state of alarm, exclaimed to Rafa, loud enough so the others could hear, that they had made a terrible mistake. While pointing at the map, he said they must’ve gotten turned around, and that they were approaching the Jacksonville they left behind the day before. The joke didn’t go over well. Rafa wasn’t in the mood and didn’t play along. There was a Jacksonville up the road, Jacksonville, North Carolina. Later, when Alvaro’s passengers saw the signs for it, they played up the joke again, feigning horror for a good laugh.

When they crossed into Virginia, one of his passengers, who was keeping track, reminded everyone they were entering the fifth state of their journey.

On the twilight leg to Washington D.C., the traffic from Richmond was heavy. Distracted and tired, Alvaro noticed that Rafa’s Oldsmobile was no longer just up ahead. He sped up, looking around, certain that he would soon spot him again. The car went quiet. Everyone turned into a lookout for the Oldsmobile. A wave of panic washed over him, realizing his fear had come true.

He hadn’t given up the search as they neared the capital. Signs for the Arlington National Cemetery reminded him of the Eternal Flame at John F. Kennedy’s grave, and then of his father — word of the assassination had reached him at his father’s wake, forever linking their deaths. The squat but massive Pentagon building came up next. The traffic was slow and dense around the Washington National Airport exit just before he crossed the Potomac River. From the bridge, they gasped at the Washington Memorial already illuminated for the night. He pulled off at the Capitol Street exit, reassuring his passengers that they would soon find Rafa and the hotel once they got to Street K. The passengers had grown dependent on the drivers, leaving all details of the trip up to them. The only help was that a couple of them agreed that Street K sounded correct.

Alvaro drove in circles trying to orient himself, figuring out that the streets were in alphabetical order. He soon got onto Street K, but something didn’t seem right. There were no hotels on the street. The consensus among the passengers was to pull up to a bar-and-grill they had spotted on a previous pass. Everyone was hungry. They would eat and get directions to the hotel.

They walked in cautiously into a mostly empty restaurant — it was a Monday night. With help from the waitress, they settled in by the window and ordered dinner, keeping an eye out on the car parked in front. The bar-and-grill quickly became an interesting sightseeing stop for the group. A jukebox by the bar played rock-and-roll music. They made fast friends with the locals, who took interest in them, asking where they were coming from, and where they were going. Most of the patrons knew about The World’s Fair. A young woman, who spoke a little Spanish, pulled up to the table, eager to help the lost tourists.

Alvaro, the designated spokesman, explained as best he could, using the few English words he knew, that he needed to find their hotel on Street K, and that there was another car. She understood ‘caravan’, saying it out loud, and soon, she was everyone’s friend. A moment later, her smile slowly turned into a cheeky laugh, grabbing Alvaro by the hand to dance to a song that had just come on the jukebox. Taken aback, but with encouragement from his companions, he followed her to a small area near the jukebox to dance to her favorite tune. He moved his lanky six-foot-one frame in rhythm, towering over the much smaller woman. Dancing had never been his forte, but compared to the ordered steps of the cumbias he knew, rock-and-roll dancing seemed a little spastic. Glancing over to the table, he noticed everyone was enjoying his moment. Even Señora Clemencia had a big smile.

After the song, Alvaro came back to the table to work on his food and directions. By this time, Alvaro had gotten the gist of the problem. It was K Street, not Street K, and there were two of them. The young woman knew how to get to the other K Street, but she was worried her instructions were too muddled for Alvaro to understand.

While the group was finishing their meal, she went outside. They saw her flag down a passing policeman on a motorcycle. They talked for a moment. She pointed at the loaded automobile, and then came back into the restaurant. She told Alvaro to come outside to get directions. The cop said it was an easy ride — facil, amigo, he said jokingly — but as he explained the route, he saw Alvaro’s confused look staring back at him. He told Alvaro, if they were finished eating, to go get the passengers, and that he would wait a few minutes to escort them to K Street and their hotel. The woman stayed with the cop while Alvaro rushed everyone to finish and settle their bill. The group called out, tankyouberymush, over and over to the young woman, shaking her hand before they piled back into the car.

Alvaro pulled out behind the motorcycle. In his rearview mirror, he saw the young woman waving from the sidewalk, so he stuck out his left hand to wave back, a moment he would never forget.

It was a quick ride to the other K Street behind the policeman. A few of the passengers called out when they spotted Rafa’s big car. He had been driving around looking for them after dropping off his passengers. Alvaro pushed on his horn to alert the cop that he had found his way, again waving good-bye out the window. The policemen raised his hand and without looking back, roared off.

Rafa was happy to see everyone again, his worry had been intensifying by the minute. The passengers were anxious to tell him about their evening adventure, the panic at losing him, their decision to stop for food, and about the helpful young woman who got Alvaro dancing. They spoke with awe about how easily she waved her hand to flag down the motorcycle cop. Of course, they couldn’t stop talking about their auspicious arrival into Washington D.C., gloating about their luck to have an official escort into town. Rafa recounted the same story from his vantage point, about his surprise at seeing Alvaro rolling down K Street with a motorcycle police escort. “That doesn’t happen to too many visitors to the capital of the United States.”

Tuesday, April 21, 1964 — Sightseeing in Washington D.C.

Spirits were refreshed after a good night’s sleep. They were now within two hundred miles of New York, having put a thousand miles behind them. Good feelings were quickly dashed by a wet and cold morning in the forties. The day was similar to those ugly rainy days common at altitude in Bogotá. Alvaro put on the two sweaters he had packed, with his light jacket on top.

From their hotel, they walked down to Lafayette Square, then past The White House, and down to the National Mall. They stared up at the Washington Monument, raindrops hitting their faces. They walked the length of the Reflecting Pool to the Lincoln Memorial. The biting wind was painful as they hurried along the long exposed plaza. At the top landing, just before the white marble steps, Alvaro turned around to look back at the Reflecting Pool, shivering as he was. He looked out across at the imposing Washington Memorial reflecting on the water. The vista astonished him, freezing him to the spot. Everything was so perfect, clean, and shiny from the rain. A gorgeous geometry of stone and spring lawns decorated with pink from the last hints of the cherry blossoms.

Tuesday, April 21, 1964 — Washington D.C. to New York

Everyone was happy to be back in a warm car after visiting the stately landmarks at the capital. They talked about how JFK’s death was present everywhere they went, like a pall over the city.

Soon enough, Baltimore, Delaware, and then Philadelphia were in the rearview mirror, the car brimming with anticipation once they crossed into New Jersey. The ninth state, they were reminded by the same passenger. One to go.

When they reached the point on the road where the Empire State Building was visible, lit up and rising in the distance, the excitement behind him reminded him of driving with a car load of antsy kids. For most of them, this was their first time in New York. As they approached the Hudson River, they were amazed by the number of criss-crossing roads carrying such a large volume of cars. They dove into the Lincoln Tunnel for so long that the passengers started claiming it must be endless. One said he hoped the tunnel didn’t spring a leak. Someone else added that all that tile made it look like the world’s largest bathroom. Then, their stomachs turned as they started rising from the depths.

When they popped out, they landed on the West Side. It was difficult for Alvaro to look around, except when stopped at the red lights, but he was attentive to what the others had seen. He was in another world, buildings leaning in over the streets, neon signs beckoning from all sides, and headlights blinding him from every direction. He circled the block to get to the New Yorker Hotel on 34th Street and Eighth Avenue, its art deco front entrance shining gold. He got out of the driver’s seat, propped his right forearm on the door to stretch his legs and take a good look around. Que chevere, he said to himself. Llegamos.

But, the night was far from over for the drivers. A snowbird was expecting his Oldsmobile in Lakewood, New Jersey, about an hour away. Alvaro followed Rafa back across the tunnel. They pushed the speed limit, hoping not to be stopped. They returned to the hotel in the Ford, exhausted and cranky, arriving just before two in the morning.

After settling into bed, Alvaro a relentless wail of sirens kept him awake. One emergency vehicle after another would drive by, the noise reaching his room on the 19th floor. He wondered how anyone could sleep in a city like New York. There was no peace. Turns out that the previous night, one of the worst subway fires raged under the city streets. The fire destroyed a number of subway cars, closing the 42nd Street Shuttle line for days, and some tracks for weeks. Emergency crews were driving up Eighth Avenue twenty-fours hours a day to restore service as soon as possible.

Wednesday, April 22, 1964 — The World’s Fair

The excited but tired tourists convened at the hotel lobby for the subway ride on the IRT Flushing Line. They rode through Queens on a packed elevated train that felt like part of the future. When they got off at Willets Point, the ramp and the entrance to the fair were even more crowded than the train. The weather was miserable, cold and rainy, in the mid forties (under 10 celsius). Alvaro, again, had both his sweaters under his jacket to keep the chill out.

At the fair, he was on his own, free to be enthralled by the pavilions displaying the latest technological advances and the accomplishments of human history. The crowds and the chilly weather couldn’t dampen his enthusiasm and amazement as he walked the grounds. He made his way to a footbridge that crossed over the Grand Central Parkway leading to the science and travel area where Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler had large installations. Perfect for a car enthusiast like him. Every stop was another revelation. He rode the Magic Skyway, a trip inside a Ford convertible from dinosaur age to the space age. There was the U.S. Royal Ferris Wheel in the shape of a giant car tire; next to that, was a building whose domed roof resembled the moon’s surface. American rocket ships were poised to launch at the United States Space Park, a very popular exhibit given the space race between the USA and CCCP was in full swing.

Despite the heavy emphasis on the future, it was the Vatican Pavilion, where Michelangelo’s Pieta was on display, that stirred him the most. He stood in front of the sculpture for a long time, waiting his turn to get closer, staring at it intensely among the crowd of onlookers. He was awed by the masterwork, taken by the image of a defeated Christ on the lap of the Virgin Mary. He couldn’t fathom how a human hand could have carved such a beautiful and faithful rendering. He had never seen anything so noble and breathtaking, so much so he started to tear up.

April 23–28, 1964 — The Return Trip

Alvaro and Rafa spent the next day in New York, taking in the sights. The day was much warmer, with pleasant temperatures to walk around.

Only Señora Clemencia accompanied the drivers back to Florida. They left on Friday. The drive was just as difficult, a torrential rainstorm followed them most of the way through Washington D.C. At one point, Alvaro was so spent from driving, that he had to pull over on the side of the highway and have Rafa take over. With only one car and two drivers, this was a new luxury. They eventually reached Miami, enjoying one leisurely day there, spending the night at the Fontainebleau Hotel before boarding a plane to Bogotá and back to real life.

Epilogue

The wonder of the 1964 World’s Fair never left Alvaro’s soul. The possibilities of human progress, and the American future, seemed unlimited. The clarion call had only grown louder. When he returned to Bogotá, he was more determined. A plan that had once seemed distant now felt within reach. Listening to stories from his passengers who had already immigrated to Florida helped mold his abstract ideas into real steps. If they had had the gumption to make the move, he was sure he had more.

It took a little more than a year after his return from the World’s Fair trip to put his plan in motion. In August 1965, he left for New York, leaving his wife and kids at his mother-in-law’s finca. Twenty months after that, we joined him to start our new life in Astoria, Queens. Flushing Meadows Corona Park became a frequent weekend destination for us. By then, the World’s Fair was long gone. The remaining artifacts sliding into disrepair and oblivion. He told us stories about the Unisphere fountain, the rockets, the country pavilions, reconstructing the abandoned and broken down structures back to their former glory with vivid recollections from his visit in 1964. When we toured the World’s Fair grounds with him, it was like floating on the Swiss Sky Ride gondola, the horizon extending in every direction.

Señora Clemencia is a pseudonym based on the tourist he remembered the most.

Mauricio Matiz writes reflections—personal stories and poems—that spring from where he lives, New York City, often touched by where he was born, Bogotá. Follow him on Twitter @AMauricioMatiz and read more of his writing at: medium.com/matiz.