The Artist as Activist in Contemporary Nicaragua, Peru and Cuba

Para leer esta historia en español, haz clic aquí.

The room turns dark and the last audience members quickly look for seats in the back of an old chapel. Careful not to trip over plastic cups full of wine, the last ones to arrive miss the circle of light being projected on the black wall in front of them. The orb grows little by little. In it, black and white silhouettes of men on horses come into focus as they charge towards a smaller hanging figure, a duck, rocking back and forth like a pendulum. The sound of someone murmuring, hardly audible at first, fills the room. The breathing turns into panting, difficult and irregular. An incredibly claustrophobic feeling transforms the room as the blurry images take over the entire wall and the sound is everywhere, and then it becomes dark and there is silence. In an altar covered in leaves and vines, Elyla appears sitting while dressed in colonial transvestism.

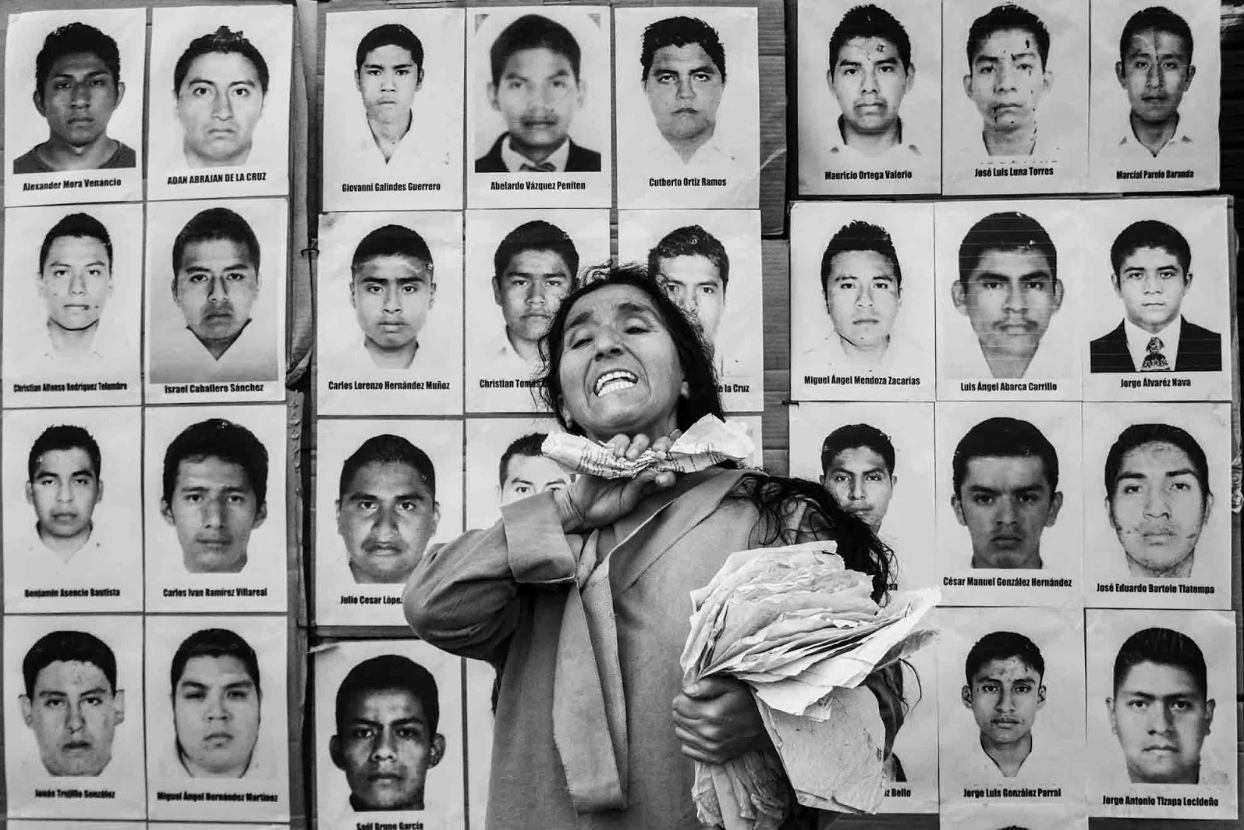

Elyla Sinvergüenza is a performance artist from Nicaragua who presented their newest piece “San Pedro – Carrera de Patos” in New York this past March 2019. The piece was different than much of their previous works, which generally form around a peregrination across streets, plazas, or other very public spaces. Long before they began an education in contemporary art, these are the spaces where they began creating performances and street interventions to communicate an immediate and unfiltered rage in response to their experiences as a queer person. When Elyla returned to Managua a few days after their performance, they were not sure what they would find. The same streets that they have used to weave together their work were still overtaken by a brutal repression that to this day has caused more than 320 deaths and forced more than 70,000 into exile. When I asked them if they believed art could provide an alternative to the current situation in Nicaragua, they answered: “The only thing that comes to mind is the line of a song by Anthony and the Johnsons that says ‘From the corpses flowers grow.’ There we are, wanting to be born, to be flowers, to be pure resistance. They can’t kill us all, thousands more of us will be born. Art is more than an alternative kind of weapon...it is a path forward and a lot of us are taking it.”

I interviewed Elyla and two other artists with the hope of getting better insight into how current artists in Latin America view their place in the worlds of art and activism. Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, a Cuban curator and art historian, worked in a governmental art gallery until she was fired for co-founding the digital platform Museo de la Disidencia (Museum of DIssidence) in Cuba. Since that moment, there has been no going back for her. She has dedicated herself to breathing new life into the concept of dissidence and cultural activism on the island, even while in exile. Atoq Ramón, a photographer and cultural producer in Peru, didn’t even consider himself an artist initially. However, his experiences as a photographer led him to document the hip-hop movement in Peru, police violence, and now, as one of the organizers of Festival Extramuros, which seeks to support and give visibility to cultural initiatives rarely included in the exclusive circle of art institutions. Before beginning the interviews, I was conscious that it would be impossible - nor even preferable - to try to make conclusions about the state of artivism in the region based on these three very different experiences. Still, I was interested in their commonalities. Each one of these artists, either through their artistic practices or actions, looks to defy the status quo and highlight themes and communities that are not do not see themselves represented in the worlds of art and politics.

Art in Latin American countries has a long history of serving as an important alternative for processing the impact of conflicts, dictatorships, and crises, but also, as a consistent method to propose more radical and inclusive realities. This purpose can be seen in the work of each one of these three artists, in addition to how they problematize the power that sometimes comes with their platform. Whether the focus is more on the activist art or artistic activism, artists, both established members or independent actors within the art and activist worlds, are in a privileged position to have a different kind of impact. As professor and writer Stephen Duncombe puts it, the objective of activism is to tear down traditional structures of power and art can impact the emotions of audiences in order to wake them up and mobilize them. The union of both strategies is what is necessary to achieve an impact, as Yanelys explains in her own experiences: “Art allows you to play with a whole imaginary that allows us to appeal and reach a wider audience, and then, with the tools that activism gives us, we can make a dent.”

This union of art and activism has an enormous emotional and historical resonance when we consider the work of artists that emerged as a response to the military dictatorships and repressive governments of the 1970s and 80s. It has inspired a growing interest among major museums to explore artists who were ignored decades ago or were considered too political, as we can see in recent exhibitions “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985” at the Brooklyn Museum, or “Perder la forma humana” and “Activismo Artístico en América Latina” at the Museo Reina Sofía. The interest and the deserved recognition is without a doubt positive for these artists. However, we can see that the same lack of recognition from mainstream art and cultural spaces plagues many individuals and collectives that currently choose art as a vehicle of change, inseparable from their political and social preoccupations. “In the world of institutional art, what takes precedence is the individual artist and his work which can only be validated if its shown in a space that is also recognized. It’s a very closed circle,” says Atoq, highlighting those issues in the cultural sector in Peru.

Elyla has been confronted simultaneously with recognition and rejection, but even in those moments, they have been able to produce works that are visually stunning and irreverent towards the powers and norms they critique. In their words, “I look for cracks where I can insert discordance and destabilize the norm.” They were one of the youngest artists to be invited to the inaugural Nicaragua Visual Arts Biennale in 2014, but was later disinvited at the last minute. At the time, the reasons they were given were confusing, but later they learned that First Lady and Vice-President Rosario Murillo had contacted the Biennale organizers directly and demanded that they not be included. Either way, Elyla carried out their planned performance called “Solo fantasía…” Their march through the historical Bolivar Avenue reflected many of the recurrent themes of their work: transvestism, fantasy, questioning the official history and reusing patriotic symbols to question their colonialist, racist and patriarchal essence. Another performance called “Yo (no) tengo miedo de tanta realidad” made reference to an old poem written by Murillo where she described her fear of small ants. In 2018, two days after the beginning of protests, the Vice-President used the same language of the poem to describe all protesters, calling them “small beings with tiny agendas, thoughts and consciousnesses.” In response, Elyla carried out a two-part performance. The first part was them walking across San Francisco, and then a second time in Mexico City, where they released more than 300 ants in front of the Nicaraguan consulate while reciting the names of killed activists, students, and social and rural leaders. Their body, completely painted in red and black for one (colors of the Sandinista party) and blue and white for the other (colors used by the conservative movement), criticized both sides of the political spectrum for their invisibilization and rejection of queer bodies. The image of the ant became a symbol of those who collectively fight and resist. Flowers, ants: visuals of resistance that repeat themselves in the work of other artists and leave their mark.

Despite their work squarely placed in the art world, Elyla recognizes that “the spaces for contemporary art or the platforms they know are extremely conservative, classists, elitist, sexist, heteronormative and colonial.” They challenge the idea that it is even possible to question it all from within mainstream art, but it remains an important objective in order to “appeal to the sensibilities and generate reflection among the people.” They recommend visiting the project Filoteos by Espira Espora, the only contemporary art school in Nicaragua that explores these challenges. Espira was a crucial place in their development as a critical artist, and had an equal impact on their “formal, informal, and street” education that helps them maintain that “insider-outsider” tension. Keeping in mind that it is very difficult to access a formal art education or have the funding to invest in an artistic practice, they highlight the importance of what has been achieved in Nicaragua: an immensely sensitive, emotional, and experimental learning process that has given shape to new and honest visual aesthetics [...] that keep forging important reflections within the culture and denouncing realities that our states want to erase.” Elyla stresses a localized art approach, making sure to spend several weeks in the area they are planning a performance, given that the community members many times collaborate with the conceptualization and production of the performance, on top of being their final audience. Even though their investigative and explorative pieces always originate from very specific personal concerns, each project requires a different form of collective creation or relational art.

Labeling the work of artists like Elyla has preoccupied many scholars and critics. There are debates about the difference between activist art and artistic activism, how to measure their impact, and the authenticity of the commitment artists have to the causes they adopt. Curator and writer Nina Felshin focused on teasing out the methods and objectives of activist art, as well as what differentiates it from institutionalized art practices in the book But is it Art? The Spirit of Art as Activism. She highlights not only their “high degree of preliminary research, organizational activity, and orientation of participants [that] is often at the heart of its collaborative methods of execution,” but also that “activist art, in both its forms and methods, is process—rather than object—or product-oriented, and it usually takes place in public sites rather than within the context of the art-world venues.” Even though the word is not used once in the book, it centers around what many now would label “artivism.”

The term “artivism” is a word that has been in use for some years and was popularized by artists with global recognition like Ai Weiwei and the band Pussy Riot. “It may seem like the perfect term to describe what I do,” says Atoq, “On one side my photography, on the other, my activism. But I’ve never defined myself that way.” Atoq goes on further to say that he didn’t feel comfortable with the term when he heard it being used for the first time in a regional gathering of Mediactivismo-Facción in Montevideo in 2014. Even now, he resists it, as he sees most initiatives from “artivists” having a closed off dynamic that involves people who already know each other and who aren’t really involved in social processes. Those that are involved, by contrast, tend to use other names.

In the beginning, rather than identify as an artist, Atoq considered himself a comunicador popular. Through his photography and visual work he wanted to create an alternative to hegemonic media channels that could reach the majority. He called what he did “counter-information.” He began this work as he got involved with the hip hop collectives of Lima, and influenced by this movement, was one of the founders of Maldeojo. Maldeojo was a photography and counter-information collective that used social media to call out the repression and criminalization of social protest. A year later, he founded Jauría, a network of documentary photographers in Lima. He began by sharing everything through social media, before quickly realizing it would not be enough. “My audience was mostly on social media, and I thought at first that I was generating a lot of change. But later I realized that I was only reaching friends and friends of friends. It was an audience around my age with very similar interests, who were already into the same things. When I realized this, I told myself that I wasn’t doing much and I started gluing photos on the street, looking to engage not only the people I knew, but also people that pass by the same public areas.” He began to make fotozines and street interventions, looking to involve those who walked through those same areas, but had never the opportunity to interact with. The visual elements were born out of a political instinct rather than an artistic one, and through them, he searched for ways to contribute to social causes and establish new forms of dialogue. This approach was clear to him until 2017 when he was shot by police and almost lost his left eye while covering a protest.

It was the beginning of the year, when Atoq found himself in the middle of a protest against the rise of toll prices. After several protesters set several toll booths on fire, the police responded by advancing with tanks, tear gas, and shooting pellets. Atoq, unable to take pictures at a distance and seeing people injured, crossed the main highways and found himself caught between the advancing police and a hill, along with most of the other protesters. He was clearly carrying the ID of a photojournalist, but, even then or because of it, he received five pellets, one to the left eye that almost made him lose visibility. A second before, Atoq captured in another way the police officer responsible: he has a photo of the man just as he takes aim. This was the only moment they faced each other. From that instant, Atoq has lived first-hand the endless labyrinth that the search for justice tends to be. Even though he has had the support of the organization Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos, no one has been sentenced and he has not received any type of help from Peru21, the news outlet he was working for at the time.

For more than a year, Atoq stopped taking photos and distanced himself from the social justice world of Peru. His role in the organization of the Festival Extramuros this past August had been his way of returning to activism and art. He sees it as a continuation of what he was doing beforehand. “As a cultural producer, I feel that I can reach a different audience, not just the ones we are close to. As a photographer I would have never been able to reach as far.” This inaugural festival consisted of the photography and character of different neighborhoods that the organizers described as “an encounter of art and community that proposes reflections and collective creation through the image.” Atoq says that before he tried to communicate through his photography and now he is trying to generate spaces for neighbors to be able to create their collective memory and share experiences that tend to be overlooked or ignored because the people live on the periphery. Like everything he has done until now, the initiative came from a personal motivation. He saw himself reflected in the participants of the festival as someone who is young, as a migrant, as the son of a Quechua-speaking woman who moved to Lima in search of different opportunities. With this new space, the festival organizers hoped to revive the interest of a younger generation for their identities and to value stories that have not been included in the official history of Peru.

The idea seeks to be nothing less than transformative. Conscious of the historical revisionism that has allowed the political class to remove any responsibility from the government and the military for the internal conflict of the 80s and 90s, Atoq is interested in the silenced or ignored stories of those affected or those who chose to take up the armed struggle. Still, he is aware that with such heavy and painful themes it is hard to keep the dialogue open. “If I want the message or the questioning to be accessible and wide-spread, I can’t always have a confrontational message. What generates dialogue is a question. I’d rather say ‘I don’t know exactly what happened, but we need to talk, we need to talk with our elders.’ Although I have a political position and ideas that are very clear, my objective is to generate dialogue. And art can do that much better than a political party that appears every five years in the neighborhood to give away things before the elections.”

Atoq maintains that although the project has received validation from universities and financial support from the Ministry of Culture, challenges arise from the tension between the objectives of the collective and those of the government. For example, the Ministry has asked them to measure their impact by counting how many people participated in their workshops. But for Atoq, the most important thing is to leave something concrete in the neighborhood after the festival is done and to add to the work that was already being done by local organizations. “As we go into these neighborhoods, we look for partnerships, we look for cultural organizations that are already doing the work. Maybe the festival won’t repeat itself. It might be that it will be just a nice experience for the neighbors, but the cultural work of these organizations is not fleeting. For us, the most important parts were the partnerships and for us to be able to say that we had an impact by adding to the work that already exists, but is not widely recognized.”

The work of artists has a particular ability to resist and problematize the labels and assumptions that renders some groups invisible and while giving more power to a select few. This ability is often born and developed through their rejection of labels that have been forced on them. In the same way that Atoq hesitates to describe himself as an artivist, many artists resist in their work and discourse to be quickly and simply labeled as Latin American artists. “One identifies as latino/a by sheer exhaustion and to not have to fight daily,” says Elyla referring to the lack of education in Nicaragua and in the United States about the history of colonialism in their country. What would be crucial for them is a process of decolonizing the education systems that render Indigenous peoples invisible and “continue propping up the power of capitalist nation-states that are colonialist, corrupt, and fascist. This is the Latin America that one confronts and that one sees as an exoticized farce by academic, artists and folklorists.” However, they also admit how difficult it is to find an alternative that “takes into account the geographic closeness, the common history, that shared cultural DNA.” They’re still searching.

For Atoq, what brings people together is uplifting shared histories, ancestral wisdom, communal practices, and celebrating that a common identity still exists and was not exterminated. When he travels, he finds it particularly important not to think as a Peruvian, but as a part of a larger collective than those defined by borders and barriers. Yanelys also echoes the importance of this common history, but warns that it does not mean that there is an automatic feeling of kinship or solidarity. “When I was in school, I was always told that Cuba had this link with Latin America, but I’ve never felt that [...] My experience when planning the #00 Bienal allowed me to learn about the struggles that other artists had in the region. I was able to talk to artists from all parts, a collective of Mexican women, el Colectivo 250 that was involved in a campaign against femicides in Mexico, Brazilians working for the recovery of a historic cultural memory, performers that worked on the theme of dissidence...I was able to understand their projects, understand what they thought and tell myself that these were the same battles.”

Comparisons that make broad generalizations about the worlds of art and cultural activism in the region fall apart easily, especially when one submerges oneself in the Cuban art world. Cuba, recognized around the world for the caliber and sheer volume of its artistic production, also has a cultural sector and institutions that award or punish based on the level of adherence an artist has to the state’s politics. The most famous instances of art censorship, like the prohibition of the movie P.M. or the Padilla case at the beginning of the Revolution, are events that independent artists are vividly aware of as they see themselves targeted by a new law, Decree 349. It has always been difficult for an independent artist to make a living outside of the parameters of the Writers and Artists Union, but with the ‘opening’ of the Cuban economy and the slow expansion of internet on the island, a generation of independent artists has emerged, eager to have larger audiences and to sell their work. They want to be and to create the alternative to the cultural sector led by the government, and they are increasingly more organized and active.

Yanelys Nuñez Leyva is one of these artists. A curator and art historian by trade, she is the cofounder of the digital platform Museo de la Disidencia, a space that seeks to recontextualize and naturalize the concept of dissidence in Cuba. She’s been involved in the organization and defense of the most important initiatives of the independent art sector in Cuba in the last few years, among them an alternative biennale, the #00 Bienal de la Habana and the campaign “Artistas cubanxs against Decreto 349” (Cuban artists against Decree 349). Her progressive path towards activism was influenced by figures such as Zona Omni Franca and Sandra Ceballos, but once she arrived, there was no turning back. “I work in the world of art and I came to activism due to necessity, after becoming conscious that there was no other way I could work,” she explains when asked if she considers herself an artist or an activist first. She doesn’t feel conflicted between these two areas of her life and stresses the potential that art has for a broader appeal and to approach themes more creatively, from a place of irony or sarcasm. She believes that artists have more liberty than political activists, since many dismiss artists as part of a romanticized category and don’t take them seriously. This turns out to be a form of “protection” that Yanelys and other individuals involved in cultural activism, like Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, Amaury Pacheco, Iris Ruiz, Estudiante Sin Semilla, Verónica Vega, José Ernesto Alonso, Yasser Castellanos among others, take advantage of. With attractive visual ideas and public interventions, she hopes to not only involve more people that are disillusioned or immobilized by apathy, but also to support other social initiatives that go beyond the art realm.

Her fight for an independent cultural sector has taken place in innumerable settings, but on July 21, 2018, it took her to the front of el Capitolio in Havana. On this occasion, she was forced to take an unexpected decision, during a protest action where the artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara planned to cover himself in human excrement to protest the new regulations announced under Decreto 349 and the refusal of the government to dialogue with artists. When Yanelys arrived it seemed that the action had finished before it started, as the artist and their collaborators had been arrested while sitting on the steps towards the Capitol among confused tourists and rushed bystanders. Caught between rage and powerlessness, she decided to take things into her own hands. Yanelys explains that there was never a plan B, but she decided to carry forth the action to ensure that those arrests hadn’t happened in vain. “I had the instinct because I wanted the arrests to have some effect. I wanted them to happen because of something we had accomplished and not something we wanted to do.” In a video she can be seen crossing the street to arrive in front of the Capitol, covered in the excrement she had brought to the site of the protests, screaming the reasons behind the protest. Unlike the other artists, she was the only one who wasn’t arrested. What they were looking to do was force some type of dialogue after being confronted with a negative from the government, and their inspiration came from a practice Cuban prisoners used, covering themselves in excrement when protesting so that police would not stop them. Yanelys said what she had to say, the story captured the attention of international media, and while still covered in shit, she left to look for her friends who had been arrested.

The action on the Capitol steps marked an important moment for the Movimiento San Isidro (San Isidro Movement),a collective that was forged in the heat of the campaign against Decree 349. Before the campaign, the group has been active organizing several events and initiatives, among them the most important being the #00 Bienal de la Habana in May 2018, a convening that brought together more than 170 artists during a ten-day program. “Even though the #00 Biennale was organized with the community in mind, we were in the homes of artists, and in one way or the other, the surrounding neighborhoods benefitted, it was a work,a political gesture that was directed to the art world and its institutions.” This event cemented purpose in the group’s conscience, and after several arrests and intimidations, prepared them to open up and achieve their next step: a campaign for the derogation of Decree 349, a law that entered into effect in December 2018 and created additional restrictions for artistic production (especially independent production or that which was considered politically “incorrect”). The campaign against the decree involved many sectors of the Cuban community, both in the country and abroad. A music video was produced, there were several public letters signed and circulated, convocations and discussions, several protest actions, protest concerts, and an invitation to collective meditation that never happened because organizers were arrested before arriving or they were kept from leaving their homes. Publications such as The Art Newspaper, Frieze, Hyperallergic, and Reuters covered these actions and recognized artists such as Coco Fusco wrote excellent reports.

The struggle to ensure that all have access to the space and privilege to create and question in Cuba, extends well into the past. Yanelys names the collective Zona Omni Franca and Sandra Ceballos’ Espacio Aglutinador as antecedents belonging to a rich tradition of artists and collectives who have used the tools of the activist world, sometimes without even knowing it, to critique institutions and provoke the art world. She had heard of Zona Omni Franca when she studied art history, but not taught from the point of view of activist art. Later she met its members and still holds an enormous respect for this autodidactic cultural collective made up mostly of black men from Alamar, an area at the periphery of Havana. They are the creators of the Festival de Poesía Sin Fin (Endless Poetry Festival) and have carved a place for themselves in the world art through “the strength of resistance.”

Through the Museo de la Disidencia, Yanelys places herself in the same lineage of action as Sandra Ceballos. Sandra is the founder and defender of Espacio Aglutinador, a gallery and laboratory for experimentation and resistance, where all or most established artists in Cuba have come through since 1994. One of its last projects was an exhibition put together in collaboration with the artist and art critic Coco Fusco. The exhibition called “Malditos de la Posguerra” (The Damned of the Postwar) “looks to rescue the artists that have been invisibilized or that were cast away if at one point they had their place within official cultural institutions.” The merit behind this work of visibilization is huge in the eyes of Yanelys. “Sandra organizes expository events, conducts research, tries to make catalogues to ensure there is a record of the exhibitions; we [Museo de la Disidencia] try to do the same through social media, trying to make it as accessible as possible, so that it doesn’t remain stuck in the art world, but is accessible online for anyone who wants to get closer to the art world and see all of this.”

The Museo de la Disidencia platform seeks to achieve this in two ways: through a process of investigation and the creation of digital archives, and by organizing activations that are connected to these archives and that target different audiences. The project Museo de Arte Políticamente Incómodo (Museum of Politically Uncomfortable Art) investigates and archives examples of dissident art from before, during, and after the Revolution, placing specific emphasis on those that have been ignored in the official history. The focus of this first stage has been to create an overview of Cuban art history by not only including works that opposed the government during the colonial period and times of the republic, but also those that opposed other forms of power, like that held by the Academy of Art. “In this process of investigation, we’ve run into the initiatives of the opposition. We’re faced with a Cuba that we did not know, that the Cuban people don’t know. Before, I had no idea there was an active opposition. Then, in this process of encounters with activists, we realized that at some point we would also be called dissidents. We decided to naturalize it and to say that being dissident is not a bad thing.” The themes that they investigate are rarely able to be researched in libraries, and are much less accessible to the general public since one cannot directly access them without special approval from an institution. So the museum has had to go to the primary source, to people who knew the artist, or those who have conducted research, but up until now have been too afraid to share their work. Each new addition to the archive is accompanied by an activation, an event that allows the project to connect with other audiences. Yanelys mentions events like “Otro Poeta Suicida” (Another Suicidal Poet), realized in collaboration with Amaury Pacheco, which appealed to a young and alternative audience, or another focused on gender-based violence, “Mi Cuerpo es Mío” (My Body is Mine), that involved a spokesperson from CENESE. Each of these events adds a new layer to the Museo de la Disidencia’s typical public, making its audience more heterogeneous. The proposals for events come from collaborators based on their interests and capacity, which ensures that they respond to a concrete interest and don’t descend into the type of ‘extractivism’ that define certain artistic initiatives.

When Yanelys speaks it is easy to notice her enthusiasm and the sense of urgency she feels to rewrite the history of art in Cuba, taking advantage of this unprecedented moment in terms of the number of public and collective actions by artists. “The history of Cuban art is not only very badly told, but has a lot of gaps and things that aren’t discussed and that can’t be published inside of Cuba.” She currently lives in Spain after being forced to go into exile at the beginning of 2019. Still, she highlights the need for “healing, forgiveness and dialogue” in a time of extremes between the opposition and those supporting the government. Her link to the Movimiento de San Isidro and the Museo de la Disidencia and her desire to continue to support artists in Cuba are unshakeable, but she admits that she is learning to navigate the difference between the opposition that is still in Cuba and those in the diaspora. “My main goal is to see how I can help my community that is still in Cuba and that I am still very much a part of. The main reason for me to be here is to find new ways to remain involved in what happens there because it’s what I know, I suffered it in my own flesh, and I can’t just remove myself simply because I’m now part of the diaspora.”

Whatever term one has heard first—artistic activism, politically engaged art, or artivism—there is a tradition with a rich history in the region and that continues despite the lack of institutional appetite for this type of artistic production currently happening in Peru, Nicaragua, Cuba and the rest of the region. Artists tend to be distrustful of terminology they see as a new trend that has little relevance to their work. On the other hand, mainstream museums show a renewed interest for what they deem artivism, but their focus is on retrospectives that elevate the profile of artists that already have their own mythology, and very few times support and bring visibility to current activist artists. This allows these cultural institutions to borrow the language of social movements with the comfort that the distance of time provides and without having to make commitments to current ideologies or to respond to the inequalities that many of these artists critique. It is a self-preservation instinct that only serves them. Meanwhile, those who follow the work of current artists such as Elyla, Atoq and Yanelys can get a much more nuanced vision of the most urgent issues in their society. It is artists like them that continue to embody the spirit of resistance and protest that is the essence of art.

Laura Kauer García is a writer, translator and human rights professional. She was born and raised in Buenos Aires, Argentina, but has lived in Washington DC, NY and is now based in London. Previously, she worked for the new initiative Artists at Risk Connection (ARC) of PEN America, providing urgent support to threatened artists, and worked at Human Rights Watch. She is pursuing an MA in Human Rights and Latin American Studies at the School of Advanced Studies of the University of London. Her research focuses on the right to free expression, the right to protest, and threats against human rights defenders, including artists and cultural practitioners. She’s an avid reader and writes primarily short fiction. She studied International Relations at American University in DC.